Dutch researchers: modal shift not going to happen

For many years, policymakers have pursued a modal shift of cargo to rail and inland shipping. However, this modal shift has not taken place. This was concluded by the Dutch Knowledge Institute for Mobility (KiM).

For decades, European and Dutch politics have been urging the logistics sector to make more use of trains and inland shipping. This shift is also referred to as a modal shift. Looking at Dutch policy in this matter, this goes back as early as 1990, when the then cabinet expressed its wish to reduce road transport. And policymakers still want the share of rail and water transport to grow at the expense of road transport. This is because it would reduce CO2 emissions and traffic jams.

In recent years, governments have spent millions to seduce shippers. One after the other subsidy project was set up. Although these various measures have certainly been useful, they have not led to a permanent modal shift, the KiM researchers write. Apparently, many companies are very fond of road transport and can hardly be convinced to use other modalities.

Small shifts

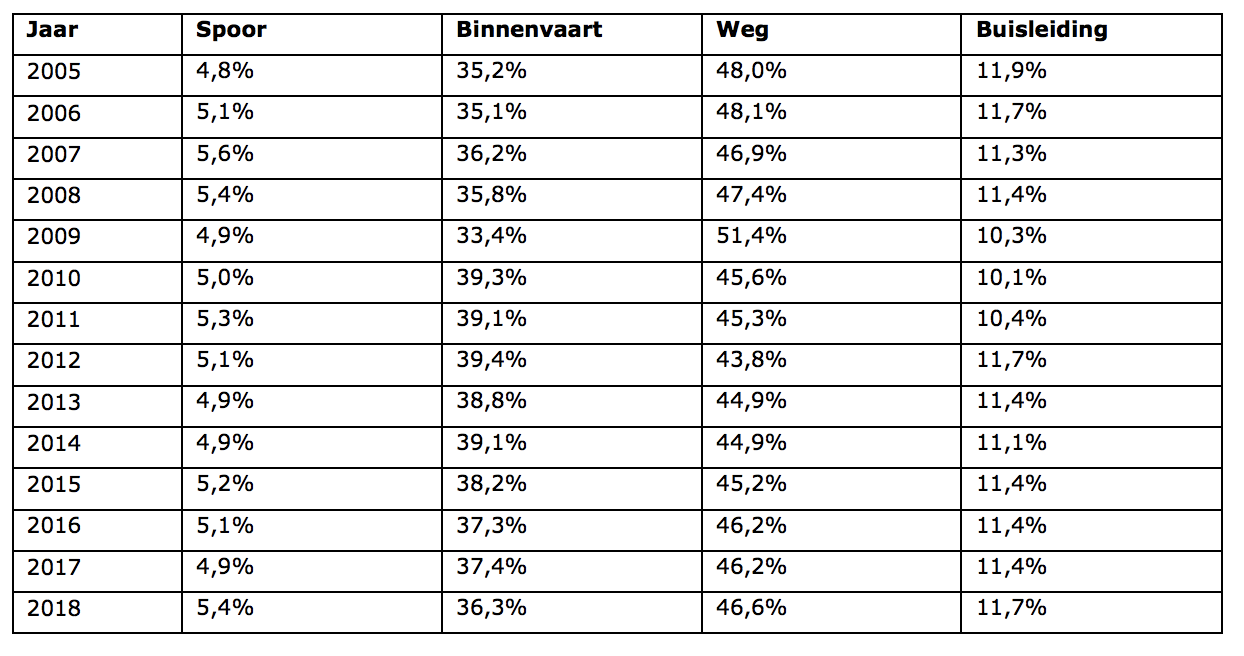

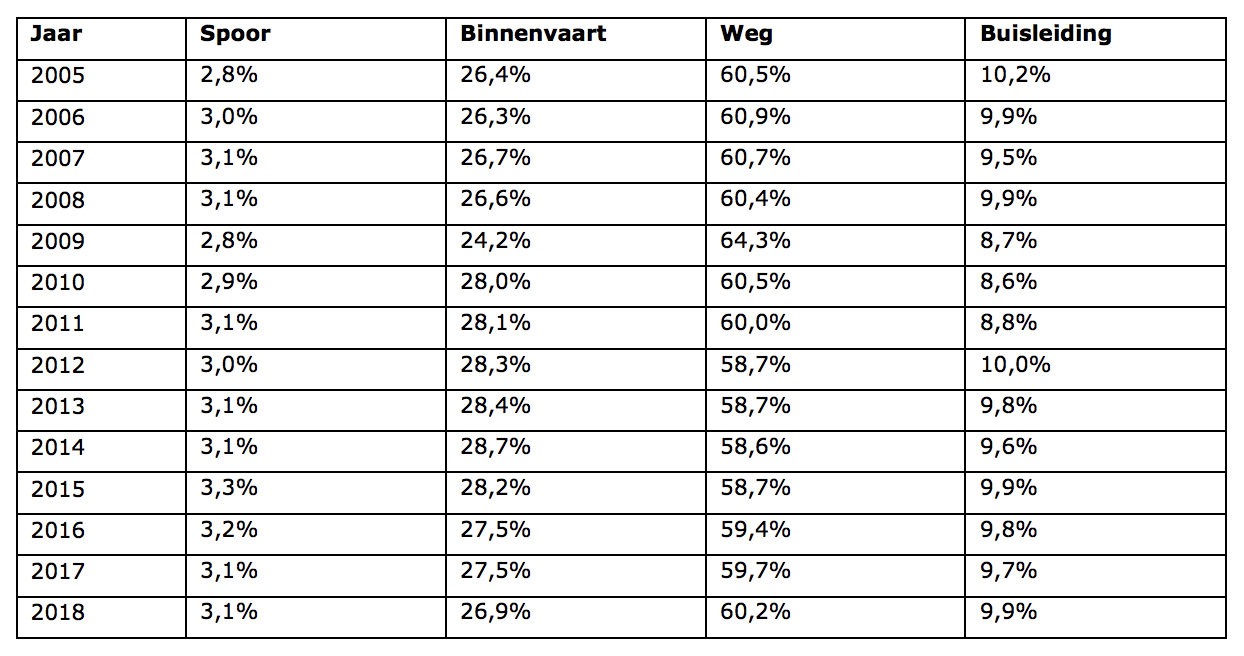

The knowledge institute has listed the modal share of the various hinterland modalities over the years 2005-2018, based on figures from Statistics Netherlands (see also Figures 1 and 2 below). These percentages vary only slightly over the years.

The distribution between the different modalities: spoor=rail, binnenvaart=barge, weg=road, buisleiding=pipes). Text continues under images.

Two trends

Roughly two trends can be discovered. Between 2005 and 2012 there was a shift of a few percentage points from road transport to inland shipping. In the years after 2012, an inverse, slightly smaller shift took place. In the latter case, there is probably no real shift. The percentages simply changed because only road transport grew in that period, while the cargo volumes on rail and inland shipping remained more or less the same.

In addition, a temporary shift was observed in the second half of 2018, moving cargo from inland shipping to road and rail transport. This was due to the persistent drought of the time. It has now become clear that this cargo was partly transported by inland shipping last year, although a part has also been permanently moved to rail, according to a report by rail manager ProRail on freight transport by train published in 2019 this year.

Causes

The reasons that a modal shift is not happening on a structural basis are diverse, and difficult to change. Some cargo, such as dry bulk, is already largely transported by water. Because of the economies of scale, barge transports this type of cargo at a lower cost. A shift to other modalities is therefore not happening.

In addition, trains and barge are not a realistic alternative for short journeys. “Over such distances, the costs of container transport can not easily, if at all, compete with the lower transport costs per tonne-kilometer of the road,” the researchers write.

“The distribution of terminals and infrastructure for freight transport also plays a role. Goods can actually only be loaded or unloaded on other modalities where a rail or inland shipping connection is an alternative to a road connection.” In addition, even when using the train or ship, in many cases part of the transport must take place by road. “A shipper who makes the switch to rail or inland shipping therefore always needs a piece of road transport.”

Feasible goal?

Is a growing share of rail and barge transport a feasible goal at all? Yes, the researchers think; but especially in the long-distance transport of containers. They refer from concrete policy recommendations. The report does come with some predictions. In the medium term (until 2024), KiM expects rail and inland shipping to see a small increase, partly due to the increasing congestion on Dutch roads.

The KiM report also quotes some predictions about the distribution between the different modalities for the longer term. In this, road transport can expect a slightly increasing volume, which amounts to approximately two thirds of the total hinterland cargo in 2050, measured in tonnes. Slightly less than a third will continue to travel via inland shipping, with the percentage possibly dropping below 30. Rail must be happy with 4 to 5 per cent of the load.

If transport by pipeline is not taken into account, the percentages for road, rail and water in 2050 hardly deviate from the distribution in recent years. Without major changes, there seems to be little of a modal shift.