UK: No prosecutions over Welsh train incident

The UK safety watchdog, the Rail Accident Investigation Branch, released its final report on track damage between Pencoed and Llanharan, in South Wales, on 6 March 2021. That thankfully low-key incident brought memories of the far better known Llangennech crash, where a freight train came off the rails and burst into flames. The memorable conflagration lit up the country and caused extensive damage to infrastructure and the environment. Similarities in the incident are the noted wheel flats on goods wagons, highlighted by RAIB

An oil train derailment will not result in any prosecutions, the safety watchdog RAIB has said in its report. The Pencoed incident, almost two years ago, was reminiscent of the much more serious crash, which saw a twenty-five-car oil train derail and burst into flames when several of the tank cars ruptured. The resulting oil spill badly damaged an area of special scientific interest. No fatalities resulted, but it was noted that the derailment had fortunately happened in a relatively isolated area.

The wheels on the train did not go round and round

The report, which runs to 46 pages, reviews the night, on the early hours of 6 March 2021, when a wagon with severe wheel flats on one wheelset fractured two rails within a mile of each other between Pencoed and Llanharan in South Wales. Although the signallers who controlled the train’s movements were aware that something was wrong with the train after the rails had been fractured, the train was allowed to continue its journey until it was stopped at Horfield Junction, on the approach to Bristol. Wheel flats were also citied in the incident leading to massive the derailment the previous year at nearby Llangennech.

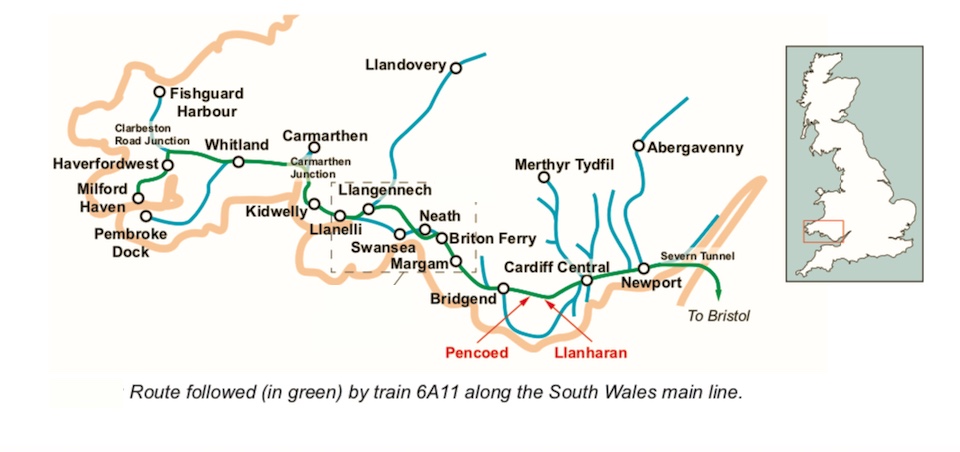

The wagon was part of train 6A11, travelling from Robeston oil terminal, at Milford Haven, on the southwest coast of Wales, to Theale oil terminal, near Reading, about twenty-five miles (40 km) from central London. The wheel flats occurred because a wheelset had stopped rotating (referred to as ‘locked’ in the report) while the train was moving during the journey. The train was on a working almost identical to the derailment of the previous year.

Rusty rails and wheelset fails

The investigation found that the wheelset had probably locked during braking in an area of very low railhead adhesion when the train was travelling along the recently reopened Swansea District line – a route, mainly for freight, which avoids the busy passenger line through Swansea, and provides a more gently graded route, suited to heavier freight movements.

The rails on that line were rusty as they had not been used for several months. The environmental conditions were such that the rails were also wet, and the combination of rust and moisture created the very low adhesion experienced by the train.

Listening for trouble from afar?

Despite taking no further action, the RAIB says the infrastructure agency Network Rail had not taken any specific precautions to ensure that an adequate level of adhesion was available when reopening the line. “This arose because Network Rail’s focus when managing low adhesion was on the autumnal leaf fall season”, says the RAIB. “It had not acted on the advice provided by a cross-industry working group on the adhesion-related precautions to take when reopening an unused line.”

The RAIB has revisited another earlier report, also in South Wales. “In light of the findings of this report”, says the RAIB, “very low adhesion may be an alternative potential causal factor of relevance to the Ferryside accident (RAIB report 17/2018). An addendum has been added to the Ferryside report discussing this potential causal factor. This update does not alter the safety recommendations made in the earlier version of the report.”

RAIB has made one recommendation to Network Rail to review its processes. It says that in light of the existing industry guidance to manage all occasions outside the leaf fall season, which could result in very low levels of wheel-to-rail adhesion. RAIB has also identified one learning point for signallers. In accordance with the appropriate railway rule book, they must arrange for a train to be stopped and examined if they become aware of an unusual noise coming from a wagon. Signallers may be forgiven for querying how that guidance may be applied – from a signalling centre that may well be in a different country – England.