Who profits from the soaring container prices?

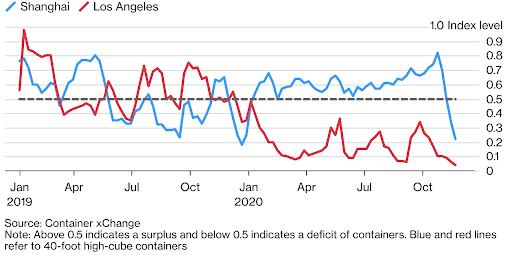

“In all my years working in this industry, I have never seen anything this crazy”, says Osmo Lahtinen, the founder of the Finnish container leasing company OVL. The ‘crazy’ refers to the different situations in terms of containers in China and Western countries. In Asia (especially China), there is a severe shortage of them, while in European and U.S ports, they pile up like mountains.

Due to this imbalance, the westbound container prices are rising dramatically. Take the route Shanghai to Rotterdam as an example. Leaving the additional costs aside, the leasing fee of a forty-foot container soared from 500 U.S. dollars to more than 1500 U.S. dollars, and the increase seems to have no upper limit. However, one question comes to mind: who is profiting from the dramatically increasing container prices?

Causes

The shortage of containers in China is ultimately caused by the import/export imbalances between east and west. Nevertheless, this inherent contradiction is not adequate for explaining the current craze.

“It is the outbreak of COVID-19 that has disrupted the supply chain order”, Lahtinen explains. “As I understand, it was a chain reaction caused by an insignificant decision. Ships carrying cargo to Europe in early January returned to China with empty containers as usual. Upon their arrival, it happened to be China’s full lockdown that was to prevent the new virus from spreading. Out of the unpromising speculation about the situation, the ships decided to carry the empty containers back and pile them up in European ports instead. As a result, ships sailed back to China empty. Perhaps it interrupted the normal flow of empty containers afterwards.”

Interpretations among the news vary. Some say before the virus became a worldwide pandemic, China reduced its export significantly due to the lockdown, leading to empty containers being stranded in Chinese ports. These empty containers were intentionally shipped back to Europe and the United States to maintain supply and demand balance. However, things changed unexpectedly a few months later. China gradually recovered from the hit, and its export volumes started surging (especially for medical supplies) while the epidemic raged in Europe and the United States. Consequently, these returned empty containers, together with the subsequent westbound containers, caused severe congestion and backlogs in European and American ports.

Suppliers

“When container prices increase, people assume that the owners must make a lot of money, but this is not the case”, said Lahtinen. For container suppliers, blocked return shipments of empty containers mean extended lease periods. In simple terms, rented containers cannot be returned in time for other clients. According to the market law, when shipping containers from Europe and the U.S to China under these conditions, the pickup fee (a one-time fee paid at the port of departure) is supposed to be paid by container suppliers. Unfortunately, the pick-up fee is growing as well.

Lahtinen says that although his company still has many containers available for one-way lease in China, balancing the surging demands among customers is now a big issue. The principle of ‘first come, first served’ is no longer viable. Sometimes, he has to figure out how to offer available containers equally to each customer to ensure fairness.

Producers

To meet the market’s growing demand, the only solution is to purchase new containers. However, the purchase of new containers requires cash flow, which causes pressure on container suppliers. Some may hold that, in this case, container manufacturers must have made a considerable profit. However, this is not true, either.

Even though China currently sees its first positive growth in container production since 2018, the capacity is still insufficient compared to the demand. Outpouring orders are already scheduled for February or even March next year. Business is growing, and so is the cost.

The steel needed by container manufacturers is mainly imported from Brazil. However, under the impact of COVID-19, the supply of iron ore shrank sharply, and its price skyrocketed. In August this year, iron ore prices rose from $83 per ton to $120 per ton, and spot prices at ports hit a historical high. According to Reuters, executives of the Brazilian steel company CSN said that from November, steel prices would get raised by 10 per cent to shift the cost pressure from raw material price increases partially. As a result, new containers’ prices are also rising, and pressure spreads across the whole transportation chain.

What happens with the ports

For European and American ports, long-term detention of ‘unnecessary cargo’ constitutes an additional problem next to the large backlog of empty boxes. Most of the retailers hope to extend the free storage time at the port. Some even delay the pickup of goods at the risk of being charged for demurrage. This general delay is not out of the retailer’s intention but mostly due to the epidemic’s impact.

Firstly, some non-essential retailers ( furniture, toys) had to close their offline stores, while the government also urged the closure of warehouses storing unnecessary goods. Confronted with unguaranteed sales and storage space constraints, these retailers chose to pay demurrage charges and pick up products only when there is demand.

Moreover, it is challenging to move containers out of the ports. This is due to the scarcity of warehouses and the reduction of operators and trucks for distribution. Owing to truck transport’s frequency limitation, some shippers tend to book more trucks than they need to ensure on-time delivery. To make matters worse, no one cancels spare trucks, which further aggravates the shortage of trucks and the goods have to be stranded in the ports.

Moreover, after unloading the cargo, empty containers are carried back by trucks to the ports, as suggested by the port operators to ease the congestion. This measure, however, further reduces the possibility of shipping empty containers back to China.

A loss for all

If anyone benefits from this, it’s probably the BCOs (Beneficial Cargo Owners). BCOs are importers able to control their cargo at customs independently with no need for third-party sources, mostly companies with a large and stable import demand. Port operators offer BCOs longer free storage time at the ports, which can be 10-20 days while the basic length is 3-4 days.

That is to say, if BCOs take advantage of the extension of free storage time and pile up their cargos at ports for more extended periods, they can reduce the cost of renting warehouses. Some believe this is one of the reasons for congestion at ports. However, port operators have now cancelled this privilege. Nonetheless, the small amounts of storage costs saved at the port are not worthy compared to the enormous costs of cross-border transportation.

“It’s a loss for all”, Lahtinen concludes. Shippers are paying surcharges for containers and shipping space. Carriers are paying extra for the priority of unloading and on-time transhipment. Container suppliers and manufacturers bear the high cost of raw materials, and ports and terminals suffer losses from cargo piles.

“We are facing a ‘black swan effect’, as no-one can predict what the epidemic has in store for the global supply chain. Only by joint efforts, will we conquer the difficulties and drive the supply chain back in track”.

You just read one of our premium articles free of charge

Want full access? Take advantage of our exclusive offer