A decade further and still the same obstacles

The Rail Freight Forward initiative and European legislative framework could offer lessons to help railways and decision-makers around the world achieve the climate change targets agreed at the recent COP24 summit in Katowice, believes Jürgen Maier, Head of International Affairs & Projects at BLS AG and BLS Cargo.

Maier is also co-ordinator of the work on ‘prioritisation, funding instruments and monitoring of TEN-T parameters’ within the Sector Statement Working Group addressing improvements in the European rail freight sector. Below is a contribution of his hand, published previously in Railway Gazette.

Rail Freight Forward

More than a decade ago,four competing rail freight operators — DBCargo, TX Logistik, SBB Cargo and BLS Cargo — decided to launch a common position paper setting out the need for better framework conditions to support the development of rail freight. The main problems identified at that time were a lack of customer focus and an unbalanced playing field compared to both rail passenger operations and road transport.

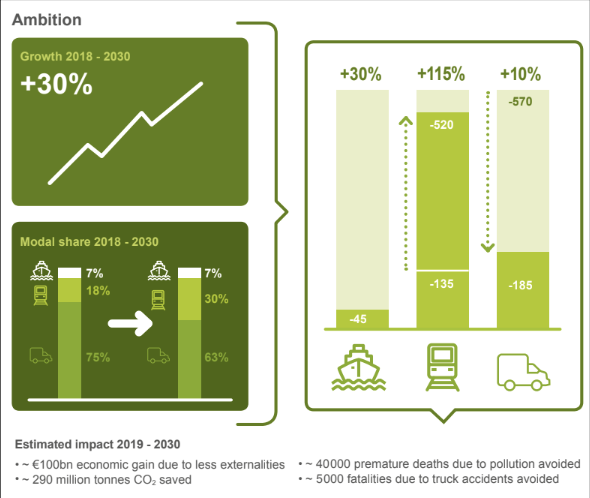

Jump forward to today, and the Rail Freight Forward initiative launched with the dispatch of Noah’s Train in December argues that many of the same obstacles are still hindering the effective development of rail freight. RFF brings together more train operators, as well as shippers and logistics sector representatives as ‘sparring partners’. The scope and ambition of the campaign is much wider. The ambitious target is that 30 per cent of all international freight traffic in Europe should be moving by rail in 2030, compared to the current average of 16 per cent to 17 per cent.

That the RFF launch was held in Katowice was no coincidence. It was timed to coincide with the United Nations-led COP24 climate conference, in order to flag up the vital role which rail freight needs to play in contributing to the battle against climate change, and the steps that are needed to bring that about.

Global climate targets

During COP24, the delegates formally adopted the so-called Paris ‘rulebook’, codifying the targets set out at the COP21 Paris conference in December 2015, where 195 countries agreed the first-ever universal, legally binding global climate deal. This set a long-term goal of keeping the increase in global average temperatures to less than 2°C above pre-industrial levels, while aiming if possible to limit the increase to below 1·5°C to minimise the impacts of climate change.

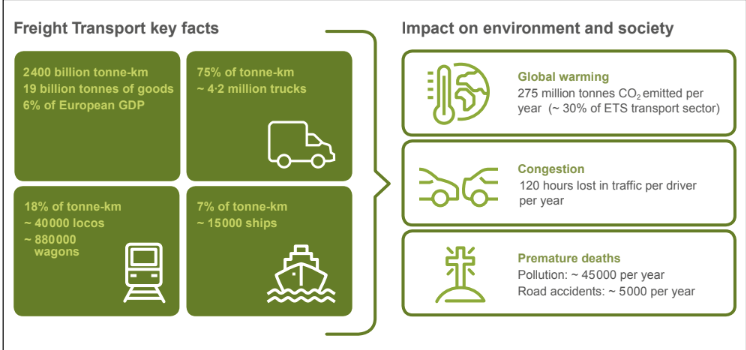

As far as Europe is concerned, the EU’s ‘nationally determined contribution’ is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 40 per cent by 2030 compared to 1990. All of the key legislation for implementing this target had been adopted by the end of 2018. However, one outcome from the Katowice talks was a hint that more ambitious climate pledges would be needed before 2020. Rail freight could be part of the answer, not just in a few countries, but right around the world. Thanks to rail’s better energy efficiency and much lower emissions per tonne-km, modal shift is a key driver in reducing the impact of freight transport, within an increasingly multimodal framework.

Legislative framework

Despite the over-riding imperative, national governments have rarely given much priority to rail freight (Fig 1). Financial support may be provided in some cases, but fair regulatory and tax treatment between modes, simplifying technical and operational rules or a sustainable financial model for investment seldom appear on the political agenda.

Nevertheless, two key elements of European legislation have helped to set the groundwork for future rail freight growth. The first of these was Regulation EU913/2010, ‘A European Rail Network for Competitive Freight’, which came into force in November 2010. This established a network of trans-European rail freight corridors, attempting to strike a balance between freight and passenger traffic in the provision of capacity and priority in line with market needs and ensuring that freight train punctuality targets could be met.

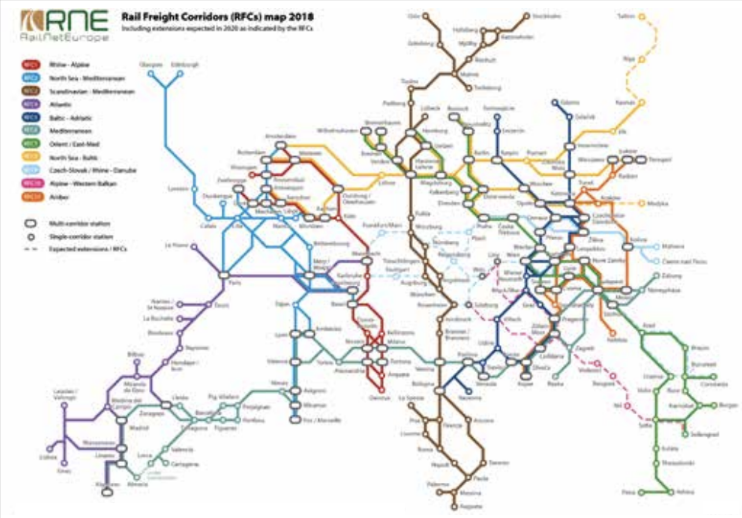

The regulation called for closer cooperation between infrastructure managers on path allocation, infrastructure development and the deployment of interoperable signalling and train control systems. The nine (now 11) rail freight corridors agreed by the European Commission and the member state transport ministries were intended to reflect current and future logistics flows (Fig 2).

Each has an Executive Board bringing together the national ministries and infrastructure managers at a strategic decision-making level and a Management Board to deal with operational issues. Integrating railway undertakings and terminal operators into the corridor management and development process was a further step to promote intermodal thinking.

The EU policy on Trans-European Networks dates back to action plans in 1990, but it was not until 2013 that most of the framework was put in place. The idea is to support the functioning of the internal market by linking regions and connecting Europe with other parts of the world. The ultimate aim of this strategy — which covers other sectors beyond transport — is to connect up national infrastructure networks and ensure interoperability by setting common standards and removing technical barriers.

In terms of transport, a truly intermodal approach would ensure that each mode plays to its strengths and the transport network operates in the most economical and environmentally friendly way. Thus it is important to connect railway corridors with roads, ports and airports, for example.

The EU enlargements of 2004 and 2007 prompted a thorough review of the Trans-European Transport Network, leading to the adoption in 2013 of nine strategic corridors as the TEN-T Core Network. These would be augmented over time by a wider Comprehensive Network. The key parameters for the TEN-T networks include a standard 740 m length for freight trains, a 22·5 tonne axleload and interoperable ETCS. A 4 m loading gauge profile to facilitate intermodal operation will be another parameter in some corridors. The nine core corridors each have a Coordinator appointed by the European Commission to set priorities and oversee progress.

Another positive step on the horizon is the granting of further powers to the EU Agency for Railways to implement a Single European Railway Area by reducing national requirements and legislation. The TEN-T policy is backed up by the Connecting Europe Facility, an EU funding instrument devised to facilitate infrastructure projects ‘of common interest’, such as removing bottlenecks and closing up missing links. The CEF budget for 2014-20 was 24 billion Euros, and the projected budget for 2021-27 is expected to be more than 33 billion Euros.

Doing the homework

Unfortunately, from the rail freight perspective, these two legislative instruments are not always aligned, and do not address all of the issues. Achieving meaningful modal shift will depend on putting in place a clear strategy which considers the requirements of all parties and the obstacles to progress.

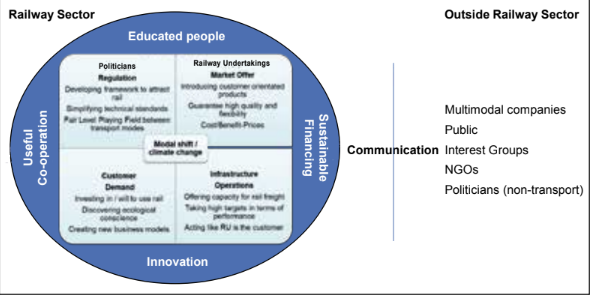

However, it is important that stakeholders should avoid taking isolated actions to optimise their own business which could risk weakening the railway system overall. Fig 3 shows the four main groups of rail freight stakeholders and their related priorities and constraints. Customers need transport at lower cost, and reliable arrival time estimates in order to coordinate deliveries with their other activities. They also need greater flexibility to handle short-term requests, an area where rail currently loses out to road haulage. Meanwhile, politicians continue to demand that railways deliver better performance and better financial results to balance the costs and benefits of public support.

Railway undertakings need sufficient high-quality train paths if they are to offer a reliable service to their customers. They are also looking for rapid implementation of new rules and standards which could help to reduce administrative and operating costs. And they need the different infrastructure managers to take a harmonised approach in managing construction works and disruption.

Infrastructure managers generally remain dependent on their national governments and national safety authority. They need to ensure sufficient funding to cover routine operations and maintenance, as well as any investment in extra capacity. At least, that is the theory. In reality, we often find that the different parties are arguing with each other over what should be prioritised. Given the contradictions, it is perhaps not surprising that each group of stakeholders tends to focus on its demands before starting to tackle its own homework. So the whole sector is losing precious time to convince end customers about the wider environmental and societal benefits of rail freight.

Four framework priorities

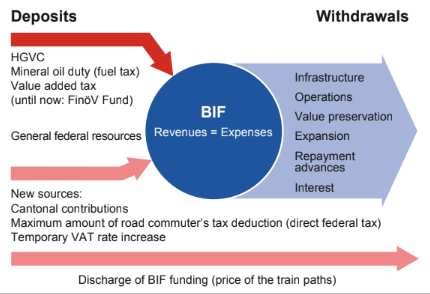

Looking ahead, a number of ‘extended’ framework conditions need to be put in place. The first of these, without a doubt, is a sustainable financing structure to guarantee reliability, quality and sustainability. As yet, most countries have not put in place a long-term financing model, which leads to difficult discussions every year about how much money should be allocated for rail. One possible instrument could be the Swiss model of a Rail Infrastructure

Fund (Fig 4) which put in place guaran- teed sources of funding to ensure a well-developed railway for the future.

However, money is only part of the challenge. A successful system needs well-educated, open-minded people to manage and develop the business efficiently. As is well known, the rail sector faces a huge bulge of retirements and the loss of skills, not just managers and engineers but also operating staff, despite the relentless march of automation. The labour market is currently unable to cover this demand, partly due to rail’s specific requirements but also because the sector suffers from an image problem.

Development of a sustainable rail system can only be achieved through greater cooperation. All players must collaborate to establish a sound foundation on which to build a competitive business. Each stakeholder should focus on their customers’ requirements, and then work together to prioritise those initiatives which bring the greatest benefits.

The fourth pillar is innovation. Everyone is talking about how disruptive technologies and digitalisation will transform the transport sector. Railways have always lived with disruption and innovation, and in their time were disruptive technology themselves. The big unanswered questions remain about what counts as innovation, and how concrete products can be realised in a realistic timeframe. How far are such new products compatible with existing technology? What are the costs, and who should cover them? A lot of good initiatives are being pursued, but in many cases the level of coordination and common understanding could usefully be improved, as well as focusing on the precise benefits.

The outside world

The rail sector can sometimes seem like a closed system, with a lot of internal discussions between the same few people, who in most cases understand the issues. But it is important not to forget the need to communicate with the outside world, and especially the wider public as well as politicians. On the one hand, it is essential to convince them of the environmental, social and economic advantages of rail, and on the other to gain support for much stronger measures to mitigate climate change.

It has become increasingly clear that the rail sector needs strong political backing. It was heartening that the national transport ministries across Europe signed the so-called ‘Rotterdam Declaration’ at the TEN-T Days event in June 2016, underlining the necessity of further improvements in rail freight and providing a clear indication that politicians supported both current and new actions. That ministerial declaration was matched by a ‘Sector Declaration’, signed by all of the railway associations and RFC management groups. This was broadly in line with the ministerial declaration, but explained some of the issues in a more detailed way.

A voluntary ‘sector statement group’, has been meeting over the past two years to discuss the actions mentioned in both declarations and draw up a ‘Top 10’ list of priorities. Each of these is led by a coordinator who assembles all the relevant information and launches initiatives on behalf of the rail freight sector. This work will continue in 2019 and 2020. The first results were reported at the Rail Freight Day event in Wien last December, alongside the ‘Wien Declaration’ renewing the ministerial commitment to making rail freight an integral part of the climate change agenda. The work of the sector statement group has helped to establish the core objectives for the Rail Freight Forward initiative (Fig 5).

Looking beyond Europe

Climate change is not simply a European issue, and the working group has been looking to learn from current initiatives around the world that could help to inform practical actions. Australia’s Inland Rail project offers a ‘once-in-a-generation’ opportunity to reshape freight movements across that country. Using a mix of upgraded lines and new connections, it will create a 1700 km north-south corridor between Melbourne and Brisbane, intersecting with the east-west Sydney – Perth corridor near Parkes, to complete the ‘spine’ of a national high-performance rail freight network.

Meanwhile, India has committed to building a network of dedicated freight railways to provide additional capacity on six of the country’s busiest rail corridors. The country’s huge population poses a real challenge in addressing the need to move goods in an efficient and sustainable way.

The 1483 km Western DFC from Mumbai to Delhi and the 1839 km Eastern DFC connecting Punjab and West Bengal have been under construction for some years and the first sections are now starting to open for traffic. Another major initiative of note has been the growth over the past few years of rail freight on the 11000 km ‘Silk Road’ route connecting China and Europe, as an increasingly attractive alternative to air or sea freight. Yet there is more work to be done. There remains the need to connect other countries in the Asian region as well as China, and here we can note the work of the Un-escap Trans-Asian Railway initiative.

A crucial issue is setting the right priorities for rail freight, which will help to focus the investment. As with Australia and India, the aim must be to achieve a high level of capacity utilisation while ensuring that rail flows can adapt to current and future market demands.

Four key recommendations

Based on my experience and work on the various corridors, I would like to put forward four recommendations that will — hopefully — help to ensure a strong future for rail freight.

1. Act in a customer-oriented way. All players want to push their own agenda, but as a first step they need to reflect how to satisfy the needs of their current and future customers.

2. Collaborate. Making efficient use of scarce resources means following a common approach, with continuous collaboration and exchange of knowledge. Everybody needs to learn to accept other opinions and compromise.

3. Communicate. Everybody inside and outside the rail sector needs to publicise success stories, both small and large. We must also highlight the obstacles that remain to be addressed, but not be afraid to do so in a self-critical way. Railway innovation is not just about the glamour of high speed passenger trains or the general drive towards digitalisation. Rail freight must draw attention to its role as an important priority in tackling climate change, explaining the broader context to the public in a more comprehensible way.

4. Deliver. We can talk and analyse endlessly, but success will only start with effective implementation of the promises, demonstrating that we can meet the end customers’ needs. This would improve the reputation of rail freight and attract additional freight volumes to rail. Then, and only then, will we really start to contribute to meeting those climate change objectives.